What to see in Fuerteventura ?

The barrillera and the cosco

Today we are so used to buying everything we want that many times we do not pay attention to its production process and even less to the raw materials that are needed for its manufacture. For example, buying a bar of soap seems like a trifle to us, and making it at home is an entertaining craft to do as a family. However, until well into the nineteenth century, the issue was different. Not all components were so easily found, nor were they within everyone’s reach.

One of the essential elements, both for making soap and for making glass, is soda. Until Nicolás Leblanc, at the end of the 18th century, did not invent artificial soda, it was extracted from various plants known as barrilleras or soseras.

Barrilla plants are halophilic plants that grow in arid places with high salinity. Both being characteristics of Fuerteventura. You just have to take a walk along the Costa Majorera to find large quantities of these plants used for the manufacture of soda: mainly barrilla and cosco.

Barrilla or frost (Mesembryanthemum crystallinum) is easily differentiated from cosco (Mesembryanthemum nodiflorum), because the latter has a very intense reddish coloration. Barrel, for its part, has very significant watery papillae on its leaves. Its flowers are also much larger and more showy than those of the cosco.

Despite these differences, both were called barrilla. They were collected and processed together.

Barrilla as the economic engine of Fuerteventura.

Barrilla plants played a fundamental role in the island’s economy. They were one of the most important economic engines of Fuerteventura. The plants were collected and dried. Once dry they burned. The ashes, very rich in alkaline salts, were compacted, forming small blocks of barreled stone, which were then loaded onto the ships.

Every year ships loaded with tons of barreled stone left for some European ports, mainly England. Ships were also chartered to the United States.

Since the beginning of the 19th century, Puerto del Rosario, Puerto Cabras at that time, became the most important port on the island, thanks to the incessant barrillera activity. There were many English ships and merchants who called in the current capital waters to negotiate with this product. Thanks to the incessant traffic of ships and commercial goods, this freight port became the capital of Fuerteventura.

Barrel trade accounted for 25% of the island’s agricultural wealth at the beginning of the 19th century. It was therefore a very lucrative activity for lands that did not support other types of cultivation. In many areas the cultivation of cereal and barrilla was combined.

There were years in which even more amount of barrilla was exported than of cereal. As an anecdotal note, it should be noted that, between 1800 and 1804, cereal was sold in Fuerteventura for a value of 6,880,000 reais of fleece, compared to 7,072,000 reais of barrilla fleece. The large profits provided by the bar trade gave rise to the smuggling and irregular traffic of this raw material. It is estimated that, in the first five years of the nineteenth century, more than 6,000,000 reales of fleece to barrilla did not go through official channels or customs, saving the payment of fees and taxes for said trade.

The collection of barrilleras plants supposed an economic boost for the most disadvantaged families, which in the case of Fuerteventura were the majority of the island. When in 1829 the García Corral brothers from Lanzarote, tenants of the dehesa de Guriamen, in La Oliva, decided to prohibit the passage of their neighbors to collect cosco and barrilla, almost 500 people from Villaverde, Los Lajares, La Oliva and Corralejo, rose in weapons against them. This historical event is known as the “Riot of Guriamen”, and its protagonist is a people subjugated to bourgeois power. The “Riot of Guriamen” has all the epic elements to become a novel when it comes to National Episode.

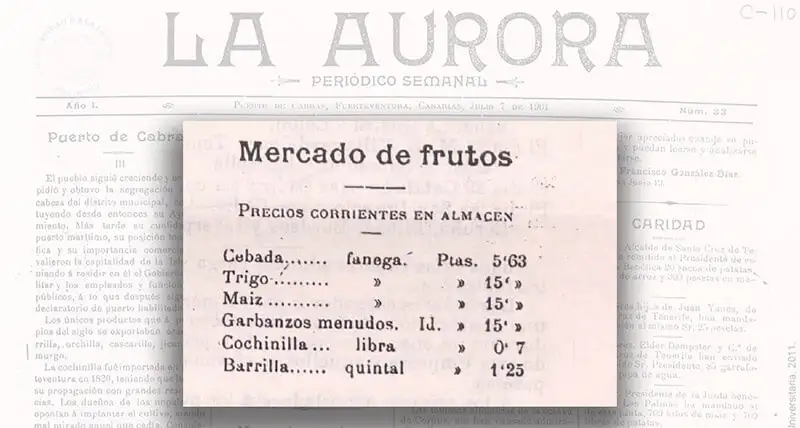

With the discovery of artificial soda, the bar trade collapsed during the second half of the 19th century, and its export came to an end. In just a few decades the price of a quintal of barreled stone plummeted

Despite the fact that ships laden with bark no longer left for England, their trade continued locally.

Barrel and cosco in food.

In times of famine, the Majorera population resorted to both the seeds of the cosco and those of the barbell to make the “gofio de cosco”. This gofio is somewhat more salty than the cereal one, but it has remarkable nutritional properties. The gofio de cosco was produced and consumed within the family. It was not traded, except on extreme occasions when it was traded for other foods. Like any other type of gofio, that of cosco, it was also taken to accompany salted fish and broths, with sugar, etc.

There were times of famine so pronounced, in Fuerteventura, in which it was even prohibited the collection of barbell and cosco to obtain soda. The bar, which had been collected, had to be distributed among the poor so that they could eat something.

Fuerteventura3 Fuerteventura8